Wantage Tanneries

Wantage Tanneries

By Sem Seabourne

The track can be heard here: Wantage Tanneries

More information about can be found here: Wantage Museum galleries

More information about Sem can be found here: Icknield Way Morris Men Sem Seabourne

The text is as follows:

The story of how Wantage went from having the largest tannery in the Kingdom to none at all within one century!

A tannery is a place where animal hides are turned into leather. Before the availability of plastics and cheap aluminium, leather was used for a huge number of industrial, agricultural and domestic applications, and at the beginning of the nineteenth century Wantage had the largest tannery in the Kingdom according to the government’s inspector, William Mavor in 1809. But by 1825 all tanning activity in Wantage had finished and by the end of the century all that remained were the large houses and cottages of the tannery owners and workers.

There is some evidence that tanning hides to produce leather was happening in Wantage in Anglo-Saxon times in an area near the church and Betjemen Lane called Tannheye. In the twelfth century Henry II granted the church in Wantage to the Abbey of Bec in Normandy and it fell within the manor of Priorshold which was the responsibility of the Priory of Ogbourne St. George. Dues were paid to the Abbot at Bec and the Prior by way of leather garments. In 1224 the Prior was granted a special licence for exporting leather goods amongst other things to the Abbot at Bec.

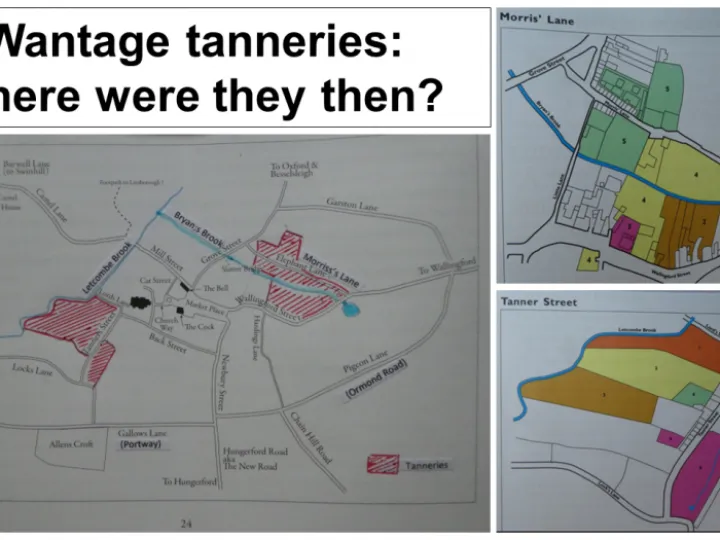

So it seems probable that leather making in Wantage may have extended over a millennium. What we know from recorded history is that in 1522 the Aldworth family were operating a tannery on the site originally known as Tannheye. The tanneries developed along the west side of what is now Priory Road, historically known as Tanner Street, in the area between the road and the Letcombe Brook.

The Aldworth family continued for a hundred and seventy years on that site but throughout the seventeenth century others started tanyards along Tanner Street, like the Goodmans, Smiths, Allens, Saunders, Stevens and Ansells. The strong, unpleasant smell from the tanneries and prevailing south-westerly wind forced a change of location around 1700 and large tanyards then developed between Wallingford Street and Morris’s Lane. The source of water was a stream called Bryan’s Brook rising from a spring where Broadway Motors garage stands today. Bryans Brook is today underground, running under the car park at Waitrose and emerging into the Letcombe Brook under Sainsbury’s car park. Morris’s Lane ran parallel with Seesen Way, the remains of it runs in front of the library.

Tanneries on the Wallingford Street site variously belonged to Nicholas Bacon, the Stevens family, Lancelot Whitfield and the Ansell family. Paul Sylvester was a tanner who came from Burford and bought up tanyards and by marrying into the Ansell family he merged tanyards into the site seen by the government inspector as the largest in the country. In all some fifty eight families were involved with tanning in Wantage over the years and at times as many as eleven separate tanneries were operating.

So why was there so much tanning activity in Wantage? Well firstly there was a good demand for leather for local agricultural use but the main reason was that all the materials needed to make leather were readily available. The starting point is the supply of hides from cattle readily available locally but also from the passing drove roads, The Ridgeway and The Icknield Way use by farmers to drive animals to market in other towns. Wantage had a number of slaughter houses, Taylor’s guide to the area says “the quantities of cattle, sheep and pigs slaughtered and transported on pack horse every week exceeding those of any other town in the south of England.”

A good water supply was essential, hence the location of the tanneries by the Letcombe and Bryan’s Brooks. Firstly, it was needed for cleaning up the skins by the fellmongers but the next stage of the process required soaking them in a slaked lime solution. There was a convenient local supply of chalk stone and limestone from the quarries and this was treated in kilns to produce quicklime or calcium oxide. When mixed with water this produced the quick-lime solution which would weaken the hairs on the hides. The hairs were scraped off to prepare the hides for the puering or bating process. The skins were soaked in a water based mixture containing dog and pigeon faeces, stale ale, urine and rotting vegetables or animal carcasses. Dogs and pigeons were kept to provide the components of this unpleasant cocktail.

Finally, the skins were put into water filled pits in layers sandwiched with oak bark dust produced from surrounding oak trees. The oak dust required replacing every month and the whole process could last nine months. After tanning the hides were pressed by a roller and dried before being sold to be prepared for their application. Many other industries evolved from the leather making, like curriers who softened the leather with fish oils, sadlers and tack makers, cordwainers or shoe makers, and glove makers.

The smell from these operation pervaded the atmosphere of Wantage and as hygiene in the abattoirs and tanneries wasn’t controlled there was associated disease. Also, with no sewerage treatment the spent contents of the pits went back into the Brook to cause problems downstream. You might ask why did the people of Wantage tolerate such activity. The answer lies in access to regular employment; around 22% of the male population of Wantage was directly employed in the tanyards and with associated activities up to a third of the population owed their livelihoods to the tanning industry.

So why did it all come to a fairly abrupt ending in 1825? Well, Paul Sylvester had invested heavily in modern technology – bark mills, drying halls, steam generators, rolling mills and so forth. His modern and expensive technology was noted by the government inspector. But, above all, Sylvester had invested in a new French process for making leather faster thereby increasing his stock turnover and profitability. Unfortunately for him the process didn’t work, the leather cracked in its applications and by 1811 he was declared bankrupt. Many of his financial backers suffered as a result and so did linked businesses like the curriers and shoemakers.

Lancelot Whitfield bought some of Sylvester’s facilities but by 1825 he was also forced to shut up shop forced by national events. Locally supplied oak was becoming scarcer and even dog faeces were being imported from turkey – bringing things from a distance added cost. The development to use lime in fertiliser pushed up the price of lime and chalkstone. Tanning represented 22% of the national economy and was a lucrative source of revenue via taxes for the government; leather duty doubled in 1812. Laws relating to leather manufacture imposed strict operating conditions which created a lack of business flexibility and when the Napoleonic wars ended in 1815 there was a huge drop in the demand for leather and this was accompanied by a slump in agriculture and industry.

Transport was improving at this time with canals and better roads but this didn’t favour Wantage where roads remained in a bad state. It did help the producers in larger cities like London and Birmingham who were now in a better position to profit from economy of scale.

So the largest tannery in the Kingdom passed into history but the houses of the tanners stand as a testimony to their endeavours. Travelling east along Wallingford Street you will first come to The Ivies opposite Post Office Lane, which was Paul Sylvester’s house, his stables were built up against Yeomanry House. Next to that is Alton House where successive families of tanners lived; namely Henry Stevens, Thomas King, Richard Rawlings and finally Lancelot Whitfield from 1790 to 1825. Further along after the Kings Arms Pub at numbers 45 to 47 is the house where the Bacon family lived when operating their tanyard in the late seventeenth century.

Tanner Street was renamed Priory Road in 1901 and the house known as Priorshold, which dates from the seventeenth century, was where the Aldworth family were based. Number 20 Priory Road also dates from this period and the cottages from numbers 22 to 30 were built to house the tanyard workers.

The Clock House in Grove Street was built when the tanneries were at their busiest and notably it has no windows or doors at the rear to protect the owners from the sight and smells of the tannery. Take a walk round and have a look at the historic houses of Wantage but try to imagine the smell that accompanied them from the largest tannery in the Kingdom.